AFRICAN AMERICAN ART

FROM THE FLOMENHAFT COLLECTION

January 5 - March 3, 2012

FROM THE FLOMENHAFT COLLECTION

January 5 - March 3, 2012

Press Release:

The Black artists’ selections on view share neither an artistic program nor a similar background. They are all of a different mettle. All create with an unremitting creative force that issues from their Black heritage, their American heritage, political or societal influences or from a poetic instinct. What is clear is that out of their shared heroic struggles have come some glorious art that feeds on life. The Flomenhaft Gallery is proud to have collected works by wonderful Black artists and is pleased to make them available to the public. In our exhibit are: Emma Amos, Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Beverly Buchanan, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, Charles Lloyd Tucker, and Carrie Mae Weems.

Atlanta born artist, Emma Amos once said “For me, a black artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.” She received her BFA at Antioch College studying fine arts and textile weaving. She also worked as an illustrator for Sesame Street and as a textile designer for the very prestigious Dorothy Liebes. She was the only female artist in the Spiral Group formed by Romare Bearden and his peers. The Spiral group recently was celebrated in a superb show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Three of Emma’s works in our exhibit are: Let Me Off Uptown, Josephine and the Ostrich and Beauty. Her pastel painting Josephine and the Ostrich (1984) is a tribute to Josephine Baker, world famed American born French dancer, singer and actress who was carried through a boulevard in Budapest, sitting aloft her carriage and pulled by an ostrich.

Benny Andrews’ ink drawing from 1974, MacDowell Colony/Across the Water, was created 10 years after Congress gave President Lyndon Johnson the right to do whatever he deemed necessary to defend South East Asia. Those ten years of bloodshed in Vietnam resulted in 50,000 American servicemen coming home in body bags, others coming home disabled, and American pilots and crews of downed aircrafts being taken to horrific prisons. With terse linear forms, Andrews drew a mother standing at the edge of a cliff screaming perhaps for her son lying dead in a pool of blood across a deep chasm, a black cloud looming above. It could just as well be a passionate depiction of any mother today bereft because of a son or daughter killed or maimed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

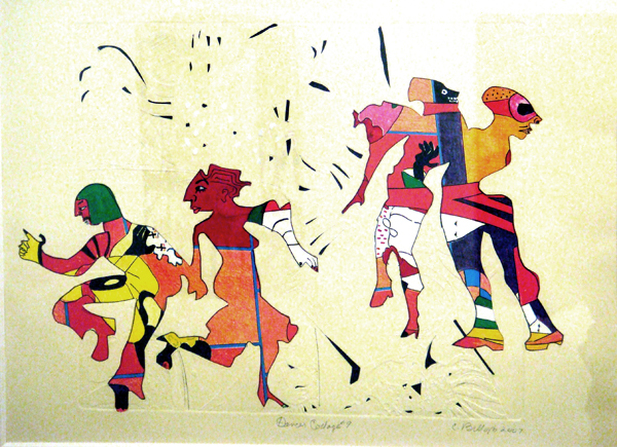

Romare Bearden was born in North Carolina in 1911 and grew up in Harlem. His centennial is currently being celebrated in many museums and galleries. His mother was actively engaged in social issues, and great black writers, musicians and politicians often visited their home. He had a degree in education, but his first love was art. He is arguably one of the great masters of the collage. It is worth making a pilgrimage to our exhibit if only to see Up at Minton’s (1980) a collage with painted elements for which Bearden is renowned. His work offers a microcosmic view of the jazz musician’s life during the Harlem Renaissance days, when after their gigs, they went to Minton’s and played their hearts out by the light of the moon. It was the work chosen by the Bearden Foundation for a picture puzzle sold in many museums and for their 2005 engagement book cover. Another work, Maternity/Ancestral Legend (1972), a watercolor and collage on board, is a metaphor for motherhood that freezes the images in our minds. When UNICEF was searching for the essence of a Black Madonna and Child for Christmas cards, at least 20 years ago, they asked to reproduce this one. It is still used as one of their holiday images.

Beverly Buchanan’s shack architecture in paintings such as Ferry Road Shacks (1988), oil pastel on paper, and her sculptures are poetic works as rich in dignity as they are in complexity. They evoke the spectra of people, places and a culture that was fast disappearing in the byways of North and South Carolina, of people that could neither read nor write but raised children who became doctors, lawyers and all sorts of creative adults. Each of her makeshift sculptures, created out of scavenged materials, she calls a “portrait,” an homage to people who may have lived in a shack, or for a friend she made along her trek. Buchanan is also a poet and for a work in our exhibit Coming Home the Back Way, wood and mixed media, 1991, she wrote a poetic legend which will be on view.

Whereas we know Jacob Lawrence best by his socially conscious art, the ink drawing on view in this collection is a nostalgic work. Done in 1961, it is entitled Chess on Broadway. The preoccupation of chess players is so carefully depicted in his boldly distinctive style and the groupings orchestrated with the perfection of angular austerity, that it is hard to imagine any artist besting this work to communicate that time, place or involvement in the game.

Faith Ringgold is the quintessential story-teller and a remarkable artist. Double Dutch on the Golden Gate Bridge (1988), which we are displaying, “is one of four quilts about being free to go and do whatever one can wish for. In this case, she has drawn young Black girls in Harlem playing a favorite after-school street game. Although Faith has transferred the game and the girls to the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco, of course it is Harlem in the background where Faith grew up.

Charles Lloyd Tucker was Bermuda’s first Black professionally trained artist and a dominant figure on the art scene during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1948 he went to London and studied at the Anglo-French Art Centre and then the Bryam Shaw School of Drawing and painting. He soaked up the culture of England and Europe, visiting art galleries always with sketchbook in hand and his talent was recognized early. When he returned to Bermuda in 1953 he started teaching at the Berkeley Institute, and inspired a generation of artists. Teaching provided him with the financial freedom to develop as an artist outside of the classroom. He was very fond of his mother, an elegant lady who loved to wear hats and probably inspired our painting, The Lady with the Hat (1960). The influence of his time spent in Europe is clear in this work. There are remote echoes of Gauguin and Modigliani, artists he must have known from his student days.

Recently, several of Carrie Mae Weems works in our exhibit were borrowed by the Tate of Liverpool for an exhibit entitled “Color.” On the subject of color, Weems says it all. From the late 1988 to early 1990 Weems created a series entitled "Colored People” which emphasized the range of skin color hidden behind the color “black.” The images portray the terms the African American community has used to create its own hierarchies by way of color. We also include a four-part suite from her Sea Island Series of 1992. To create a new kind of historical and cultural chronicle, she visited the unique African American folk of the Gullah dialect who inhabit the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina. Our work evokes the superstitions of the Gullah people. This is an important part of African American history because these people were cut off from the melting pot of the mainland and retained a purer version of original customs, language, games and song.

The Black artists’ selections on view share neither an artistic program nor a similar background. They are all of a different mettle. All create with an unremitting creative force that issues from their Black heritage, their American heritage, political or societal influences or from a poetic instinct. What is clear is that out of their shared heroic struggles have come some glorious art that feeds on life. The Flomenhaft Gallery is proud to have collected works by wonderful Black artists and is pleased to make them available to the public. In our exhibit are: Emma Amos, Benny Andrews, Romare Bearden, Beverly Buchanan, Jacob Lawrence, Faith Ringgold, Charles Lloyd Tucker, and Carrie Mae Weems.

Atlanta born artist, Emma Amos once said “For me, a black artist, to walk into the studio is a political act.” She received her BFA at Antioch College studying fine arts and textile weaving. She also worked as an illustrator for Sesame Street and as a textile designer for the very prestigious Dorothy Liebes. She was the only female artist in the Spiral Group formed by Romare Bearden and his peers. The Spiral group recently was celebrated in a superb show at the Studio Museum in Harlem. Three of Emma’s works in our exhibit are: Let Me Off Uptown, Josephine and the Ostrich and Beauty. Her pastel painting Josephine and the Ostrich (1984) is a tribute to Josephine Baker, world famed American born French dancer, singer and actress who was carried through a boulevard in Budapest, sitting aloft her carriage and pulled by an ostrich.

Benny Andrews’ ink drawing from 1974, MacDowell Colony/Across the Water, was created 10 years after Congress gave President Lyndon Johnson the right to do whatever he deemed necessary to defend South East Asia. Those ten years of bloodshed in Vietnam resulted in 50,000 American servicemen coming home in body bags, others coming home disabled, and American pilots and crews of downed aircrafts being taken to horrific prisons. With terse linear forms, Andrews drew a mother standing at the edge of a cliff screaming perhaps for her son lying dead in a pool of blood across a deep chasm, a black cloud looming above. It could just as well be a passionate depiction of any mother today bereft because of a son or daughter killed or maimed in Iraq or Afghanistan.

Romare Bearden was born in North Carolina in 1911 and grew up in Harlem. His centennial is currently being celebrated in many museums and galleries. His mother was actively engaged in social issues, and great black writers, musicians and politicians often visited their home. He had a degree in education, but his first love was art. He is arguably one of the great masters of the collage. It is worth making a pilgrimage to our exhibit if only to see Up at Minton’s (1980) a collage with painted elements for which Bearden is renowned. His work offers a microcosmic view of the jazz musician’s life during the Harlem Renaissance days, when after their gigs, they went to Minton’s and played their hearts out by the light of the moon. It was the work chosen by the Bearden Foundation for a picture puzzle sold in many museums and for their 2005 engagement book cover. Another work, Maternity/Ancestral Legend (1972), a watercolor and collage on board, is a metaphor for motherhood that freezes the images in our minds. When UNICEF was searching for the essence of a Black Madonna and Child for Christmas cards, at least 20 years ago, they asked to reproduce this one. It is still used as one of their holiday images.

Beverly Buchanan’s shack architecture in paintings such as Ferry Road Shacks (1988), oil pastel on paper, and her sculptures are poetic works as rich in dignity as they are in complexity. They evoke the spectra of people, places and a culture that was fast disappearing in the byways of North and South Carolina, of people that could neither read nor write but raised children who became doctors, lawyers and all sorts of creative adults. Each of her makeshift sculptures, created out of scavenged materials, she calls a “portrait,” an homage to people who may have lived in a shack, or for a friend she made along her trek. Buchanan is also a poet and for a work in our exhibit Coming Home the Back Way, wood and mixed media, 1991, she wrote a poetic legend which will be on view.

Whereas we know Jacob Lawrence best by his socially conscious art, the ink drawing on view in this collection is a nostalgic work. Done in 1961, it is entitled Chess on Broadway. The preoccupation of chess players is so carefully depicted in his boldly distinctive style and the groupings orchestrated with the perfection of angular austerity, that it is hard to imagine any artist besting this work to communicate that time, place or involvement in the game.

Faith Ringgold is the quintessential story-teller and a remarkable artist. Double Dutch on the Golden Gate Bridge (1988), which we are displaying, “is one of four quilts about being free to go and do whatever one can wish for. In this case, she has drawn young Black girls in Harlem playing a favorite after-school street game. Although Faith has transferred the game and the girls to the Golden Gate Bridge of San Francisco, of course it is Harlem in the background where Faith grew up.

Charles Lloyd Tucker was Bermuda’s first Black professionally trained artist and a dominant figure on the art scene during the 1950s and 1960s. In 1948 he went to London and studied at the Anglo-French Art Centre and then the Bryam Shaw School of Drawing and painting. He soaked up the culture of England and Europe, visiting art galleries always with sketchbook in hand and his talent was recognized early. When he returned to Bermuda in 1953 he started teaching at the Berkeley Institute, and inspired a generation of artists. Teaching provided him with the financial freedom to develop as an artist outside of the classroom. He was very fond of his mother, an elegant lady who loved to wear hats and probably inspired our painting, The Lady with the Hat (1960). The influence of his time spent in Europe is clear in this work. There are remote echoes of Gauguin and Modigliani, artists he must have known from his student days.

Recently, several of Carrie Mae Weems works in our exhibit were borrowed by the Tate of Liverpool for an exhibit entitled “Color.” On the subject of color, Weems says it all. From the late 1988 to early 1990 Weems created a series entitled "Colored People” which emphasized the range of skin color hidden behind the color “black.” The images portray the terms the African American community has used to create its own hierarchies by way of color. We also include a four-part suite from her Sea Island Series of 1992. To create a new kind of historical and cultural chronicle, she visited the unique African American folk of the Gullah dialect who inhabit the Sea Islands of Georgia and South Carolina. Our work evokes the superstitions of the Gullah people. This is an important part of African American history because these people were cut off from the melting pot of the mainland and retained a purer version of original customs, language, games and song.

View Artwork

| african_american_press_release.pdf | |

| File Size: | 683 kb |

| File Type: | |